- Home

- W. Somerset Maugham

Merry Go Round Page 16

Merry Go Round Read online

Page 16

'What!' cried Miss Ley.

'His mother doesn't give him enough money, and I manage to help him. He pays all the bills with notes I give, and I pretend to think there's never any change. Oh, I hate and despise him, and yet if he left me I think I should die.'

Hiding her face in her hands, she wept irresistibly. Miss Ley meditated. In a moment Mrs Castillyon looked up, clenching her fists.

'And now when I go to him he'll abuse me like a fishwife because I suggested Rochester. He'll say it was my fault that we came here. Oh, I wish we'd never come; I knew it was madness. I wish I'd never set eyes on him.'

'But why did you hit upon Rochester?' asked Miss Ley.

'Don't you remember Basil Kent talked about it? I thought no one ever came here, and Paul said wild-horses wouldn't drag him. That settled it.'

'Basil must apply his aesthetic theories to less accessible places,' murmured Miss Ley. 'For that is why I came also. You know, our place is not far from here, and I've been staying at Tercanbury.'

'I forgot that.'

For a little while they remained silent. The hotel dining-room, with most of the lights extinguished, the tables clear but for white table-cloths, was gloomy and depressing. Mrs Castillyon shuddered as painfully she took in the scene, and dimly felt that this passion, which had seemed so wonderful, in Miss Ley's eyes must appear most sordid and mean.

'Can't you help me at all?' she moaned.

'Why don't you break with Reggie altogether?' asked Miss Ley. 'I know him pretty well, and I don't think he will ever bring you much happiness.'

'I wish I had the strength.'

Miss Ley gently placed her hand on the thin, jewelled fingers of the unhappy woman.

'Let me take you up to London tonight, my dear.'

Mrs Castillyon looked at her with tear-filled eyes.

'Not tonight,' she begged. 'Give me till Monday, and then I'll break with him altogether.'

'It must be now or never. Don't you think it had better be now?'

None would have thought that Miss Ley's cold voice was capable of such persuasive tenderness.

'Very well,' said Mrs Castillyon, utterly exhausted. 'I'll go and tell Reggie.'

'If he raises any objection, say that I make it a condition of holding my tongue.'

'Much he'll care!' replied Mrs Castillyon, with a sob of anger.

She went away, but immediately returned.

'He's gone,' she said.

'Gone?'

'Without a word. All the things are out of his room. He's always been a coward, and he's just run away.'

'And left you to pay the bill. How like dear Reggie!'

'You're right, Miss Ley: no good can come of the whole thing. This is the end. I'll drop him. Take me up to London, and I promise you I'll never see him again. I will try from now to do my duty to Paul.'

Their traps were soon collected, and they caught the last train to town. Mrs Castillyon sat in the corner of the carriage, her face woebegone and white against the blue cushions; she looked out into the night and never spoke. Her companion meditated.

'I wonder what there is in respectability,' she thought, 'that I should take such pains to lead back that woman to its dull, complacent paths. She's a poor creature, and I don't suppose she's worth the trouble; and I haven't seen Rochester after all. But I must take great care, I'm becoming quite a censor of morals, and soon I shall grow positively tedious.'

She glanced at the pretty woman, looking then so old and worn, the powder on her cheeks emphasizing their wan hollow-ness. She was crying silently.

'I wonder if that beast Frank knew all the time, and basely kept the secret.'

When at last they drew near London, Mrs Castillyon roused herself. She turned to her friend with a sort of despairing scorn.

'You're fond of aphorisms, Miss Ley,' she said. 'Here's one that I've found out for myself: One can despise no one so intensely as the person one loves with all one's heart.'

'Frank can say what he likes,' answered the other, 'but there's nothing like mortal pain for making people entertaining.'

A few days later Miss Ley, who prided herself that she made plans only for the pleasure of breaking them, started for Italy.

PART TWO

1

MISS LEY returned to England at the end of February. Unlike the most of her compatriots, she did not go abroad to see the friends with whom she spent much time at home; and though Bella and Herbert Field were at Naples, Mrs Murray in Rome, she took care systematically to avoid them. Rather was it her practice to cultivate chance acquaintance, for she thought the English in foreign lands betrayed their idiosyncrasies with a pleasant and edifying frankness. In Venice, for example, or at Capri, the delectable isle, romance might be seized as it were in the act, and all manner of oddities were displayed with a most diverting effrontery. In those places you meet middle-aged pairs, uncertainly related, whose vehement adventures startle the decorum of a previous generation. You discover how queer may be the most conventional, how ordinary the most eccentric. Miss Ley, with her discreet knack for extracting confidence, after her own staid fashion enjoyed herself immensely. She listened to the strange confessions of men who for their souls' sake had abandoned the greatness of the world, and now spoke of their past zeal with indulgent irony; of women who for love had been willing to break down the very pillars of heaven, and now shrugged their shoulders in amused recollection of passion long since dead.

'Well, what have you fresh to tell me?' asked Frank, having met Miss Ley at Victoria, when he sat down to dinner in Old Queen Street.

'Nothing much. But I've noticed that when pleasure has exhausted a man he's convinced that he has exhausted pleasure; then he tells you gravely that nothing can satisfy the human heart.'

But Frank had more important news than this, for Jenny, a week before, was delivered of a still-born child, and had been so ill that it was thought she could not recover. Now, however, the worst was over, and if nothing untoward befell she might be expected slowly to regain health.

'How does Basil take it?' asked Miss Ley.

'He says very little. He's grown silent of late, but I'm afraid he's quite heart-broken. You know how enormously he looked forward to the baby.'

'D'you think he's fond of his wife?'

'He's very kind to her. No one could have been gentler than he after the catastrophe. I think she was the more cut up of the two. You see, she looked upon it as the reason of their marriage – and he's doing his best to comfort her.'

'I must go down and see them. And now tell me about Mrs Castillyon.'

'I haven't set eyes on her for ages.'

Miss Ley observed Frank with deliberation. She wondered if he knew of the affair with Reggie Bassett, but, though eager to discuss it, would not risk to divulge a secret. In point of fact, he was familiar with all the circumstances, but it amused him to counterfeit ignorance that he might see how Miss Ley guided the conversation to the point she wanted. She spoke of the Dean of Tercanbury, of Bella and her husband; then, as though by chance, mentioned Reggie. But the twinkling of Frank's eyes told her that he was laughing at her stratagem.

'You brute!' she cried. 'Why didn't you tell me all about it, instead of letting me discover the thing by accident?'

'My sex suggests to me certain elementary notions of honour, Miss Ley.'

'You needn't add priggishness to your other detestable vices. How did you know they were carrying on in this way?'

'The amiable youth told me. There are very few men who can refrain from boasting of their conquests, and certainly Reggie isn't one of them.'

'You don't know Hugh Kearon, do you? He's had affairs all over Europe, and the most notorious was with a foreign Princess who shall be nameless. I think she would have bored him to death if he hadn't been able to flourish ostentatiously a handkerchief with a royal crown in the corner and a large initial.'

Miss Ley then gave her account of the visit to Rochester, and certainly made of it a very neat and entertaini

ng story.

'And did you think for a moment that this would be the end of the business?' asked Frank ironically.

'Don't be spiteful because I hoped for the best.'

'Dear Miss Ley, the bigger blackguard a man is, the more devoted are his lady-loves. It's only when a man is decent and treats women as if they were human beings that he has a rough time of it'

'You know nothing about these things, Frank,' retorted Miss Ley. 'Pray give me the facts, and the philosophical conclusions I can draw for myself.'

'Well, Reggie has a natural aptitude for dealing with the sex. I heard all about your excursion to Rochester, and went so far as to assure him that you wouldn't tell his mamma. He perceived that he hadn't cut a very heroic figure, so he mounted the high horse, and full of virtuous indignation, for a month took no notice whatever of Mrs Castillyon. Then she wrote most humbly begging him to forgive her; and this, I understand, he graciously did. He came to see me, flung the letter on the table, and said: "There, my boy, if anyone asks you, say that what I don't know about women ain't worth knowing." Two days later he appeared with a gold cigarette-case!'

'What did you say to him?'

' "One of these days you'll come the very devil of a cropper."'

'You showed wisdom and emphasis. I hope with all my heart he will.'

'I don't imagine things are going very smoothly,' proceeded Frank. 'Reggie tells me she leads him a deuce of a life, and he's growing restive. It appears to be no joke to have a woman desperately in love with you. And then, he's never been on such familiar terms with a person of quality, and he's shocked by her vulgarity. Her behaviour seems often to outrage his sense of decorum.'

'Isn't that like an Englishman! He cultivates propriety even in the immoral.'

Then Miss Ley asked Frank about himself, but they had corresponded with diligence, and he had little to tell. The work at St Luke's went on monotonously – lectures to students three times a week, and out-patients on Wednesday and Saturday. People were beginning to come to his consulting-room in Harley Street, and he looked forward, without great enthusiasm, to the future of a fashionable physician.

'And are you in love?'

'You know I shall never permit my affections to wander so long as you remain single,' he answered, laughing.

'Beware I don't take you at your word, and drag you by the hair of your head to the altar. Have I no rival?'

'Well, if you press me, I will confess.'

'Monster, what is her name?'

'Bilharzia hoematobi.'

'Good heavens!'

'It's a parasite I'm studying. I think authorities are all wrong about it. They've not got its life-history right, and the stuff they believe about the way people catch it is sheer footle.'

'It doesn't sound frightfully thrilling to me, and I'm under the impression you're only trumping it up to conceal some scandalous amour with a ballet-girl.'

Miss Ley's visit to Barnes seemed welcome neither to Jenny nor to Basil, who looked harassed and unhappy, and only with a visible effort assumed a cheerful manner when he addressed his wife. Jenny was still in bed, very weak and ill, but Miss Ley, who had never before seen her, was surprised at her great beauty; her face, whiter than the pillows against which it rested, had a very touching pathos, and notwithstanding all that had gone before, that winsome, innocent sweetness which has occasioned the comparison of English maidens to the English rose. The observant woman noticed also the painful, questioning anxiety with which Jenny continually glanced at her husband, as though pitifully dreading some unmerited reproach.

'I hope you like my wife,' said Basil, when he accompanied Miss Ley downstairs.

'Poor thing! She seems to me like a lovely bird imprisoned by fate within the four walls of practical life, who should by rights sing careless songs under the open skies. I'm afraid you'll be very unkind to her.'

'Why?' he asked, not without resentment.

'My dear, you'll make her live up to your blue china teapot. The world might be so much happier if people wouldn't insist on acting up to their principles.'

Mrs Bush had been hurriedly sent for when Jenny's condition seemed dangerous, but in her distress and excitement had sought comfort in Basil's whisky bottle to such an extent that he was obliged to beg her to return to her own home. The scene was not edifying. Surmising an alcoholic tendency, Kent, two or three days after her arrival, locked the sideboard and removed the key. But in a little while the servant came to him.

'If you please, sir, Mrs Bush says, can she 'ave the whisky; she's not feelin' very well.'

'I'll go to her.'

Mrs Bush sat in the dining-room with folded hands, doing her utmost to express on a healthy countenance maternal anxiety, indisposition, and ruffled dignity. She was not vastly pleased to see her son-in-law instead of the expected maid.

'Oh, is that you, Basil?' she said. 'I can't find the sideboard key anywhere, and I'm that upset I must 'ave a little drop of something.'

'I wouldn't if I were you, Mrs Bush. You're much better without it.'

'Oh, indeed!' she answered, bristling. 'P'raps you know more about me inside feelings than I do myself. I'll just trouble you to give me the key, young man, and look sharp about it. I'm not a woman to be put upon by anyone, and I tell you straight.'

'I'm very sorry, but I think you've had quite enough to drink. Jenny may want you, and you would be wise to keep sober.'

'D'you mean to insinuate that I've 'ad more than I can carry?'

'I wouldn't go quite so far as that,' he answered, smiling.

'Thank you for nothing,' cried Mrs Bush indignantly. 'And I should be obliged if you wouldn't laugh at me, and I must say it's very 'eartless with me daughter lying ill in her bedroom. I'm very much upset, and I did think you'd treat me like a lady; but you never 'ave, Mr Kent – no, not even the first time I come here. Oh, I 'aven't forgot, so don't you think I have. A sixpenny 'alfpenny teapot was good enough for me; but when your lady friend come in out pops the silver, and I don't believe for a moment it's real silver. Blood's all very well, Mr Kent, but what I say is, give me manners. You're a nice young feller, you are, to grudge me a little drop of spirits when me poor daughter's on her death-bed. I wouldn't stay another minute in this 'ouse if it wasn't for 'er.'

'I was going to suggest it would be better if you returned to your happy home in Crouch End,' answered Basil, when the good woman stopped to take breath.

'Were you indeed! Well, we'll just see what Jenny 'as to say to that. I suppose my daughter is mistress in 'er own 'ouse.'

Mrs Bush started to her feet and made for the door, but Basil stood with his back against it.

'I can't allow you to go to her now. I don't think you're in a fit state.'

'D'you think I'm going to let you prevent me? Get out of my way, young man.'

Basil, more disgusted than out of temper, looked at the angry creature with a cold scorn which was not easy to stomach.

'I'm sorry to hurt your feelings, Mrs Bush, but I think you'd better leave this house at once. Fanny will put your things together. I'm going to Jenny's room, and I forbid you to come to it. I expect you to be gone in half an hour.'

He turned on his heel, leaving Mrs Bush furious, but intimidated. She was so used to have her own way that opposition took her aback, and Basil's manner did not suggest that he would easily suffer contradiction. But she made up her mind, whatever the consequences, to force her way into Jenny's room, and there set out her grievance. She had not done repeating to herself what she would say, when the servant entered to state that, according to her master's order, she had packed the things. Jenny's mother started up indignantly, but pride forbade her to let the maid see she was turned out.

'Quite right, Fanny! This isn't the 'ouse that a lady would stay in; and I pity you, my dear, for 'aving a master like my son in-law. You can tell 'im, with my compliments, that he's no gentleman.'

Jenny, who was asleep, woke at the slamming of the front-door.

'What's that?'

she asked.

'Your mother has gone away, dearest. D'you mind?'

She looked at him quickly, divining from knowledge of her parent's character that some quarrel had occurred, and anxious to see that Basil was not annoyed. She gave him her hand.

'No; I'm glad. I want to be alone with you. I don't want anyone to come between us.'

He bent down and kissed her, and she put her arms round his neck.

'You're not angry with me because the baby died?'

'My darling, how could I be?'

'Say that you don't regret having married me.'

Jenny, realizing by now that Basil had married her only on account of the child, was filled with abject terror; his interests were so different from hers (and she had but gradually come to understand how great was the separation between them) that the longed-for son alone seemed able to preserve to her Basil's affection. It was the mother he loved, and now he might bitterly repent his haste, for it seemed she had forced marriage upon him by false pretences. The chief tie that bound them was severed, and though with meek gratitude accepting the attentions suggested by his kindness, she asked herself with aching heart what would happen on her recovery.

Time passed, and Jenny, though ever pale and listless, grew strong enough to leave her room. It was proposed that in a little while she should go with her sister for a month to Brighton. Basil's work prevented him from leaving London for long, but he promised to run down for the week-end. One afternoon he came home in high spirits, having just received from his publishers a letter to say that his book had found favour, and would be issued in the coming spring. It seemed the first step to the renown he sought. He found James Bush, his brother-in-law, seated with Jenny, and in his elation greeted him with unusual cordiality; but James lacked his usual facetious flow of conversation, and wore, indeed, a hang-dog air which at another time would have excited Basil's attention. He took his leave at once, and then Basil noticed that Jenny was much disturbed. Though he knew nothing for certain, he had an idea that the family of Bush came to his wife when they were in financial straits, but from the beginning had decided that such inevitable claims must be satisfied. He preferred, however, to ignore the help which Jenny gave, and when she asked for some small sum beyond her allowance, handed it without question.

The Skeptical Romancer: Selected Travel Writing

The Skeptical Romancer: Selected Travel Writing The Summing Up

The Summing Up Up at the Villa

Up at the Villa The Razor's Edge

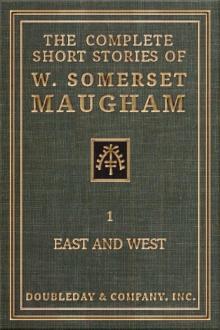

The Razor's Edge The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham: East and West (Vol. 1 of 2))

The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham: East and West (Vol. 1 of 2)) Cosmopolitans

Cosmopolitans 65 Short Stories

65 Short Stories Ah King (Works of W. Somerset Maugham)

Ah King (Works of W. Somerset Maugham) Collected Short Stories: Volume 1

Collected Short Stories: Volume 1 Collected Short Stories Volume 2

Collected Short Stories Volume 2 The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham - II - The World Over

The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham - II - The World Over Collected Short Stories Volume 4

Collected Short Stories Volume 4 Theatre

Theatre Short Stories

Short Stories Then and Now

Then and Now The Favorite Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham

The Favorite Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham Of Human Bondage

Of Human Bondage The Magician

The Magician The Great Exotic Novels and Short Stories of Somerset Maugham

The Great Exotic Novels and Short Stories of Somerset Maugham A Writer's Notebook

A Writer's Notebook Christmas Holiday

Christmas Holiday The Making of a Saint

The Making of a Saint Merry Go Round

Merry Go Round The Narrow Corner

The Narrow Corner Collected Short Stories Volume 3

Collected Short Stories Volume 3 Ten Novels and Their Authors

Ten Novels and Their Authors Ashenden

Ashenden The Moon and Sixpence

The Moon and Sixpence Cakes and Ale

Cakes and Ale Liza of Lambeth

Liza of Lambeth The Land of Promise: A Comedy in Four Acts (1922)

The Land of Promise: A Comedy in Four Acts (1922) A Writer's Notebook (Vintage International)

A Writer's Notebook (Vintage International) Orientations

Orientations Selected Masterpieces

Selected Masterpieces Mrs Craddock

Mrs Craddock The Skeptical Romancer

The Skeptical Romancer On a Chinese Screen

On a Chinese Screen (1941) Up at the Villa

(1941) Up at the Villa The Great Novels and Short Stories of Somerset Maugham

The Great Novels and Short Stories of Somerset Maugham Ah King

Ah King The Explorer

The Explorer The Skeptical Romancer: Selected Travel Writing (Vintage Departures)

The Skeptical Romancer: Selected Travel Writing (Vintage Departures) The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham - I - East and West

The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham - I - East and West